What is the point of the “natural order” if the world appears to operate in chaos? Can we change our role, our destiny, or are we servants to a greater calling? What is courage in war? What is fear? Is there a difference between the two or are they companions of a sort?

What is the point of the “natural order” if the world appears to operate in chaos? Can we change our role, our destiny, or are we servants to a greater calling? What is courage in war? What is fear? Is there a difference between the two or are they companions of a sort?

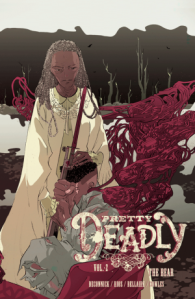

These are only some of the questions the second arc of Pretty Deadly poses.

None of them have clear answers. Well, most of them.

What I admire about Pretty Deadly and its creative team of writer Kelly Sue DeConnick, artist Emma Rios, colorist Jordie Bellaire, and letterer Clayton Cowles is the ambiguity, deliberate or otherwise. We ask big questions all the time, drilling our own psyche on ideas too vast and nuanced to have an ultimate, or, at the very least, satisfying conclusion. Art is one of many platforms we use to tackle those questions; making sense of what seems impossible to understand and still we only scratch the surface. Pretty Deadly‘s sophomore tale doesn’t worry itself with definitive answers. Instead it lives and breathes in a realm where equilibrium is constantly in flux, allowing for even the smallest action by the smallest of creatures to alter the course of events.

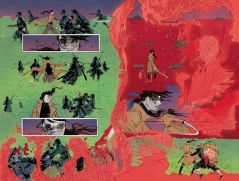

Before diving in, however, it’s important to acknowledge the craftsmanship of Rios, Bellaire, and Cowles on the unique and devastatingly powerful images in this book. In case you didn’t know, it’s gorgeous! Rios is a master of implied motion, which make for some amazing fight sequences, but it’s in her two-page layouts and splash pages where the enormity of her talent is on full display. Her repetition of patterns is stunning, specifically the gnarled rivulets of blood that feed the faceless Reaper of War contrasted with the intertwining branches and brambles of Sissy’s pastoral realm. It’s life and death performing the same dance. Equally strong and unique is the color palette, which Bellaire turns into its own form of storytelling. The heavy blues of the WWI trenches hauntingly contrasts with  the bright green of oncoming mustard gas and the heightened red of the War Reaper so well that when they all come together the clash of color amplifies the intensity of the wartime setting. And Cowles’s skill as a letterer remains a constant and vital component of the storytelling process; one bubble out-of-place and the flow stops, the mood dies, the story falls flat. These three artists, combined with DeConnick’s prose, make Pretty Deadly what it is, a piece of art.

the bright green of oncoming mustard gas and the heightened red of the War Reaper so well that when they all come together the clash of color amplifies the intensity of the wartime setting. And Cowles’s skill as a letterer remains a constant and vital component of the storytelling process; one bubble out-of-place and the flow stops, the mood dies, the story falls flat. These three artists, combined with DeConnick’s prose, make Pretty Deadly what it is, a piece of art.

That being said, the plot goeth thusly: It’s been about twenty years since the events of the first arc and Sarah Fields is on her deathbed. Fox, now a Reaper, arrives to bring her to the flourishing World Garden but Sarah’s daughter pleads for more time to give her baby brother Cyrus a chance to return home and see Sarah before she dies. Unfortunately, Cyrus is fighting in the trenches of France and the errant Reaper of War has him and his fellow soldiers in his sights. Devastated by the flood of deaths, Sissy sends her Reapers to protect Cyrus and end the war.

Man on the Run

The themes of change and adaptation are mapped out from the very beginning. Still engaging in their stories in the Soul Garden, Deathbones Bunny and Butterfly happen upon a bee. Bunny just barely recognizes her noting that she was once a nurse but is now a forager for her hive. When Butterfly asks why Bunny didn’t recognize her old friend, Bunny replies, “Her changing role has changed her.” When Butterfly asks how, Bunny remarks, “It’s changed her body. We are all shaped by what we do.” Fittingly, the words hover below the approaching Sissy, Death Incarnate, whose body changed when she embraced her role in the natural order and who, in turn, changed the Soul of the World.

Her story finds its parallel in Cyrus as the young man contemplates the chaotic world around him. Like Sissy before him, Cyrus is hesitant to embrace his future. He may not be a supernatural Ascendant, but the unknown of a war-torn world inspires just as much fear and anxiety. And with that anxiety comes a crisis of identity. Throughout the story, but more specifically under the gentle razzing of his fellow soldiers, Cyrus is identified by several nicknames and personality traits. His home in the American West and affinity with horses make him a “Cowboy” while his mile-long, dreamy gaze into the moon dubs him “Moon-Man.” In his protest of the Cowboy moniker, a  French soldier teases that he’s a knight searching for adventure and nobility, noting that his kindly treatment of a mouse in the trenches indicates he has a soft heart. Though he protests being called soft, Cyrus self-identifies with the horse that knocked him in the head. He’s a runner, willing to go halfway around the world to escape whatever it is that spooked him.

French soldier teases that he’s a knight searching for adventure and nobility, noting that his kindly treatment of a mouse in the trenches indicates he has a soft heart. Though he protests being called soft, Cyrus self-identifies with the horse that knocked him in the head. He’s a runner, willing to go halfway around the world to escape whatever it is that spooked him.

What becomes apparent by the story’s end is that Cyrus is the sum of his disparate identities and, like Sissy, it’s only when he understands how they work in tandem that he is able to make the greatest impact. As the Knight with a soft heart the mouse he kept alive goes on to spook the corrupted Reaper of Fear, a ghostly horse mounted by the Reaper of War, causing Fear to buck War from his back, severing his heightened power. And as the Cowboy and the Runner, he forms a bond with the equine reaper, easing his anger and calming him enough to send him into the fray once again. This time on the side of the better angels, so to speak. These facets of Cyrus culminate in his true calling, a final identity, the Reaper of Courage. Like the bee, like Sissy, Cyrus is given cause to adapt in the wake of change. It makes good on the Moon-Man name as well – an apparition of bravery in battle riding a mount made of eerie moonlight.

Always Two There Are

Duality plays a significant role in the world of Pretty Deadly. In the first arc, Fox and Death’s parallel treatment of Beauty led to one’s downfall and the other’s redemption. Their shared story served as a window into the state of the supernatural world and how the previous Death had subverted the natural order. The second arc offers a similar window, this time into the machinations of the Reapers. They ride in pairs, though their partnerships fall somewhere between the complimentary and the combative. Molly Raven and Johnny Coyote are the Reapers of Good and Bad Luck, though it’s never quite clear which is which. Deathface Ginny is the Reaper of Vengeance and Big Alice is the Reaper of Cruelty, which doesn’t sound like a good fit until one considers that vengeance can easily turn to cruelty and cruelty can be conducted in the name of vengeance given the right circumstances. If anything, Ginny and Alice keep each other in check. The creation of these dynamic duos, however, is essential to understanding how they operate and how they influence each other and the mortals around them.

The setup leads to the big reveal that the Reaper of War’s gas-mask toting horse is actually the Reaper of Fear and it’s their spurious partnership that keeps blood spilling on the battlefield. A veiled metaphor for the incomprehensible death and destruction surrounding WWI, War’s success lies in his corruption of Fear, taking away the flight instinct of otherwise sane men and leaving only the push to fight. It fuels his blood lust and the fervor of war experienced by soldiers, without a healthy sense of fear, ensures that Sissy’s garden of souls remains unnervingly full. When War is thrown from his mount, thanks to Cyrus’s mouse with an assist from Molly Raven, Fear is free of his control. It’s when Cyrus calms the spectral stallion, though, that he becomes the Reaper of Courage. Yes, he masters Fear, but he also respects it with an understanding that Fear is necessary, if not vital, to survival. Through the symbiotic partnership of Courage and Fear, sanity appears to have returned. For a while, at least. Duality, however, goes beyond the Reapers and is constantly reinforced through the discussion and presence of more relatable and “observable” concepts like luck and fear.

God Bless the Cowards

Thematically, fear presents an intriguing obstacle within Pretty Deadly. Its manifestation as a horse rings true considering the quiet, almost calm, exterior of such a majestic beast can easily swing towards panicked outbursts in a split second. How we interpret fear and our response to that interpretation makes all the difference, which DeConnick and Rios capture beautifully as Ginny struggles to overcome her potentially mortal wound delivered by War. She’s hindered, however, by the suffocating spiral that fear creates in dire situations. Beautifully rendered by Rios, we see Ginny fold into herself, naked and afraid, falling into an abyss of her own mind. The focus on her hands gives her struggle a visceral quality as she tries to claw her way out despite the weight of fears dragging her down. She manages to snap out of her fugue, but only because Molly Raven’s warning is so sudden and startling. It’s the power of fear, which makes our ability to surmount it all the more courageous. But is courage only found in overcoming fear or is there just as much, if not more, courage in acting on fear?

There’s a fascinating moment, probably my favorite of the series, between two nurses discussing cowardice. The two are clearing the battlefield of bodies but one, Claudia, can’t stop crying over the thought that the soldiers – brave, young men – died alone and afraid. The other nurse, let’s call her Kelly (wink, wink), rebukes the idea that fear is something to be pitied. Instead, Kelly praises fear, commenting that there’d be more living men if they’d had the good sense to be afraid sooner. She drives her point home with the example of German soldiers opting for mutiny instead of drowning in a sinking ship. Not only did they save their own lives out of fear of death, but their actions turned the tide of the war by sending the Kaiser on the run. It’s also worth mentioning that this nurse sports one of my favorite expressions in the whole book.

Like Inside Out‘s conclusion that Sadness is a necessary and healthy part of growing up, Pretty Deadly turns Fear into a facet of heroism, subverting the typically conditioned response of patriotism in wartime. Courage and cowardice are two sides of the same coin. They exist simultaneously, but we make the conscious choice to interpret them one way or the other. Claudia calls Kelly’s notion that cowardice should be praised “disgusting” because her idea of heroism and courage can’t accommodate a positive place for fear. We claim to support our troops, but it’s amazing how fast that support turns to opposition over any perceived cowardice. The very thought that someone wouldn’t want to sacrifice themselves becomes offensive when it’s really more disheartening that we measure bravery based on that willingness. The conversation between Claudia and Kelly could easily be shifted from the trenches of France in 1918 to the blast walls of Afghanistan in 2015 and remain relevant.

Chaos, Luck, and the Like

One of the many reasons I admire Kelly Sue DeConnick is her fearlessness when it comes to storytelling. She’s willing to kill her darlings, but there’s always purpose behind the loss. The events of this book, however, have the feeling of a preemptive strike, a means of preparation and reassurance from DeConnick that something else is in the works. For the time being, though, this is the story that needs to be told.

Once again, the opening pages set the tone for the second act of this four-part story. The perceived chaotic madness of the bee hive troubles Butterfly, but Bunny is quick to remind her that order isn’t so easily seen except in hindsight. As the story progresses, the nature of luck is explored through the parable of the Lucky Farmer. Roughly told by Molly Raven to Johnny Coyote, then retold by Bunny to Butterfly, the story within a story posits that luck is neither good nor bad until the story ends. In fact, it’s both at the same time; a construct used to make sense of what cannot be explained but only takes on meaning after the fact.

same time; a construct used to make sense of what cannot be explained but only takes on meaning after the fact.

As the story of the farmer unfolds, the ups and downs of war play out. Cyrus and his fellow soldiers fight the enemy and the Reaper of War’s influence with each moment punctuated by a similar occurrence of good or bad luck within the parable. As readers we believe we have a certain amount of savvy when it comes to storytelling and the rules of drama, which makes Cyrus’s death that much more excruciating despite DeConnick’s early warning of his impending demise. There’s a cinematic quality to the writing and the art that gives us hope Cyrus will survive. It’s a war movie, right? Surely the hero survives since so much effort was made by Sissy and all of her Reapers to get him home?

The salve on the wound, however, is the nebulous duality of this world as seen in the spiritual hymn recited at the beginning and the end of the arc. With Sarah close to death, the wording and imagery takes on a menacing, fearful tone as flames engulf the people sitting vigil outside her home. But by the end of the story, when Cyrus arrives to help usher his mother into the afterlife, the hymn becomes a joyful eulogy as a ghostly mist fills the panels. Like the Farmer’s luck, like our perceptions of fear, Sarah’s passing is both a time for mourning and a time for celebration of a life long-lived. How we frame it alters the tone. Cyrus is dead, but he “lives” on as the Reaper of Courage. Will more come of his new role? Or does his story end here? It remains unknown until the next event and, like the Lucky Farmer, Pretty Deadly has yet to have its ending.

One has to wonder, though, if the world, or Ginny, could possibly survive without Big Alice? And does Alice’s absence mean Fox, the Reaper of Grace, and Ginny are destined for a dynamic duo of their own? Would there be any survivors of such a pairing? We’ll have to wait to find out.