Why eight questions? Because I had more than five and less than ten! Actually, there are more than eight because of grouping the questions by subject but – and you probably don’t care about any explanation I provide.

Moving on!

Over the summer I started reading more prose fiction to shake things up between comic book trades and I was fortunate to come across a spectacular, mostly coming-of-age, story of magic, music, and the harsh reality of growing up: Signal to Noise by Silvia Moreno-Garcia. Set in Mexico City and jumping between 1988 and 2009, Signal to Noise follows Mercedes “Meche” Vega who discovers her love of music, and the right vinyl, can cast magic spells. Roping in her friends Sebastian  and Daniela, the trio use magic to change their lives for the better, but the consequences of their actions result in a decades long estrangement.

and Daniela, the trio use magic to change their lives for the better, but the consequences of their actions result in a decades long estrangement.

The book comes highly recommended by io9’s Charlie Jane Anders and I couldn’t agree with her more. Signal to Noise is an intimate look at a young woman searching for a solid foundation, something she can believe in, trust in, but always comes up short. Meche’s exterior and interior turmoil makes for a complex and nuanced protagonist who is as frustrating as she is sympathetic.

In light of my new found book to gush over, I reached out to Silvia Moreno-Garcia and she was kind enough to answer several questions, via email, about Signal to Noise and her forth-coming anthology, She Walks in Shadows, which looks at the works of H.P. Lovecraft through his female characters – or lack thereof.

Maniacal Geek (MG): Though Signal to Noise is a coming-of-age story, the magical elements are secondary, acting more as a catalyst than being a consistently present force. Is this how you perceive the role of magic in urban fantasy or did it just serve this specific story?

Silvia Moreno-Garcia (SMG): For many Anglo writers and readers magic must work as a system, a kind of D&D system. I wanted to play with this notion, with how much you can systematize magic, versus the ‘magic’ which appears in Latin American fiction which works in a completely different matter. So that the result is this is not quite magic realism and not quite urban fantasy.

MG: Meche’s grandmother doesn’t mind telling stories about magic but she’s reluctant to use it and only does so to save Sebastian from Meche’s recklessness. In your opinion, is magic the folly of youth?

SMG: I leave it up to the reader to figure that out.

MG: Music is the connective tissue that keeps Meche tied to her father and becomes her means of casting spells. What is your relationship with music and how did it influence Signal to Noise?

SMG: My parents both worked in radio stations. That’s the kind of environment I grew up in. We had a lot of albums stacked around the house. I used my father’s professional tape recorder to make mixtapes. That kind of thing. My son now has a portable record player. My grandfather was also a radio announcer so the fear is it’s genetic.

MG: (Silly question alert!) Which album would be your object of power?

SMG: Josh Joplin’s Useful Music.

MG: Coming from a comic book background myself, there’s been an ongoing discussion about the flawed female protagonist, which Meche definitely fits. Were you worried that people might not be able to relate to Meche? Do we have to relate to a character like Meche? How do you feel Meche has grown as a character by the end of the book?

SMG: Ugh. Relatable, likeable characters, eh? There are so many famous characters in books you can’t relate to and the books do just fine. You have criminals like Tom Ripley and Dexter in multiple novels. And in the romance novel the brooding hero is a staple. I don’t find Heathcliff or Mr. Rochester to be relatable since I’m not a white billionaire living in the age of carriages. They’re not super likeable either, mad wife in attic and all. But women. Ah, we are much harder on women. Women better be fucking perfect and relatable.

Look, I’m Mexican, I grew up without a lot of the bells and whistles Americans take for granted. There’s not a lot of people I can relate to in books. Not Holden from Catcher in the Rye, not Bella in Twilight. So *I* can relate to Meche.

So no, I didn’t worry that Meche was likeable or relatable, although I’ve heard from many people that they can relate to her. If people find her interesting enough to follow her through the book I think that’s enough.

As to how she’s grown, I went to visit my friend who is now living in NY this year and I hadn’t been there in about 14 years. At one point he said something which sounds pretty accurate. He said: “Silvia, we are older but not more mature.” I’ll leave it at that.

MG: Do you believe Mexico has a greater cultural connection to magic? To music?

SMG: I grew up with a lot of folklore in my life and folk magic, but I believe this is unusual and certainly much more unusual for people younger than me. But you do see magic more openly, there is a witch’s market in Mexico City where you can buy ingredients, there was an “esoteric plaza” in a shopping mall near my home, and there’s the witches in Catemaco who are quite famous. Some people still might visit the curandero, the healer, or believe in the evil eye. Things like that. But the influence of Anglo culture is erasing a lot of that.

MG: You’ve edited several anthologies with horror themes with many specifically focused on H.P. Lovecraft’s mythos. What attracts you to Lovecraft and the horror genre? Do you have a favorite Lovecraft story?

SMG: “The Colour out of Space.” My thesis work focuses on Lovecraft, eugenics and women so I’m interested in him on an academic level and at a visceral one. I like all kinds of genres and read indiscriminately, from cheap, old pulp crime novels to modern dramatic lit. As a writer, horror is just one tool I can employ. As a reader, I’ve always had a basic interest in terrible things.

MG: The latest anthology, She Walks in Shadows, explores Lovecraft through the feminine perspective and the explicit or ambiguously defined female characters. In your opinion does Lovecraft have an inherent feminist slant or did you see his writings as a challenge, something to meet head on for the anthology?

SMG: He barely has any women in his stories, so it’s a challenge. The writers are all showing a variety of visions of Lovecraftian characters, Weird fiction, and women. Women for Lovecraft exist as an absence, an unnamed presence, they are the lurking fear of his stories and we are bringing them to the forefront.

If you’d like to get your grubby mits on all of Silvia’s work currently available for purchase:

Signal to Noise: http://www.silviamoreno-garcia.com/blog/books/signal-to-noise/

Love and Other Poisons: http://www.silviamoreno-garcia.com/blog/bibliography/love-other-poisons/

You can also pre-order She Walks in Shadows and follow Silvia on Twitter!

Last week we said goodbye to the citizens of Pawnee, Indiana as Parks and Recreation took its final bow with promises of an even greater future for Leslie Knope (Amy Poehler) and company in the fictional reality where we all want to live. Seriously, after seven seasons who wouldn’t want this glorious female warrior in charge of the country?  At the same time the first, but hopefully not last, season of Marvel’s Agent Carter ended with Peggy Carter (Hayley Atwell), after saving New York City from another villainous attempt at bombing the Big Apple, reaffirming her stance as a woman who knows her value to the world even if it isn’t reciprocated. Though these two shows are dissimilar in regards to genre, setting, and time period, their commonality lies in the driven, passionate, and independent women at the helm.

At the same time the first, but hopefully not last, season of Marvel’s Agent Carter ended with Peggy Carter (Hayley Atwell), after saving New York City from another villainous attempt at bombing the Big Apple, reaffirming her stance as a woman who knows her value to the world even if it isn’t reciprocated. Though these two shows are dissimilar in regards to genre, setting, and time period, their commonality lies in the driven, passionate, and independent women at the helm.

When looking at Leslie Knope and Peggy Carter it’s easy to assume that gender is their one uniting factor. How else would a modern-day Mid-Western civil servant share any similarities with a British ex-pat intelligence agent in post-WWII New York? And that’s before you add in the science-fiction, superhero element that practically pushes Agent Carter as far from Parks and Rec, genre wise, as possible. But fear not, you beautiful tropical fish. Yes, gender is a factor in comparing Leslie and Peggy, but it’s really about how their respective worlds perceive women, their response as women, and the impact that has on the viewing audience that matters. Leslie may be navigating the modern world of middle-American politics but Peggy’s struggle for acceptance and acknowledgement is just as relatable. These are women who’ve dedicated their lives to serving their native/adopted country regardless of their rank within the system. Though they may desire more, it’s how they face their obstacles that earns them the respect, loyalty, and friendship of those around them and affects the most change.

Though we’ve only had eight episodes of Agent Carter, Peggy’s importance to the Marvel Cinematic Universe has been apparent since a skinny kid from the Lower East Side took his first steps towards being Captain America. One of the premiere officers of Army intelligence during WWII, Peggy held her own in the boys club of the military, earning the respect of the men she worked with through her tenacity and resolve on the battlefield. In the trenches, she was more than just Cap’s sort-of girlfriend. The harsh reality of “civilian” life post-war, however, is that in the eyes of her colleagues in the Strategic Scientific Reserve (SSR) she’s only viewed as Cap’s girlfriend with many of her accomplishments in the field overlooked or just plain ignored. The frustration of watching Agent Carter is the accuracy of its blatant and subtle sexism and the knowledge that there really isn’t an end point. There’s no light at the end of the tunnel where we can definitively say women gained all the respect and equality. It’s not just the attitudes of post-war culture, it’s a parallel of the modern day struggles of women in the workforce. Think about it. Women are still fighting for equal wages.

Though we’ve only had eight episodes of Agent Carter, Peggy’s importance to the Marvel Cinematic Universe has been apparent since a skinny kid from the Lower East Side took his first steps towards being Captain America. One of the premiere officers of Army intelligence during WWII, Peggy held her own in the boys club of the military, earning the respect of the men she worked with through her tenacity and resolve on the battlefield. In the trenches, she was more than just Cap’s sort-of girlfriend. The harsh reality of “civilian” life post-war, however, is that in the eyes of her colleagues in the Strategic Scientific Reserve (SSR) she’s only viewed as Cap’s girlfriend with many of her accomplishments in the field overlooked or just plain ignored. The frustration of watching Agent Carter is the accuracy of its blatant and subtle sexism and the knowledge that there really isn’t an end point. There’s no light at the end of the tunnel where we can definitively say women gained all the respect and equality. It’s not just the attitudes of post-war culture, it’s a parallel of the modern day struggles of women in the workforce. Think about it. Women are still fighting for equal wages.

Still. In 2015.

Even the basic assumptions made about women in the show are mirrors of current workplace and online cultures.  Consider two of Peggy’s colleagues, Jack Thompson and Daniel Sousa. Like Peggy, they’re war veterans, but the two approach the SSR’s sole female agent in very different ways. Thompson is all bravado, a blatant chauvinist who can’t even bother to get Peggy’s name right so long as he gets his coffee and lunch order placed correctly. Sousa, on the other hand, is more sympathetic to Peggy since he’s also the target of Thompson’s jibes because of his injury during the war. And while Sousa attempts to be the good guy, telling Jack to back off and treat Peggy with more respect, Peggy calls him on his white-knighting. He may think he’s doing the right thing, being a better man than the others, but there’s a more subtle form of sexism occurring. Peggy doesn’t need Sousa to come to her aid, she’s perfectly capable of defending herself. Assuming she needs defending is just another way of reinforcing the gender stereotype that women are incapable of taking care of themselves. In fact, the underestimation of women plays throughout the entire series as virtually every female character uses their perceived weakness to their advantage against men. Dottie hides the cold, Russian assassin behind a helpless doe-eyed mid-Western persona, Angie starts spilling fake tears to distract Thompson and Sousa, and Peggy frequently makes use of her invisibility within the agency as she conducts her side investigation into clearing Howard Stark. Though she’s loathe to use her second-tier status, it’s a tool nonetheless. It’s actually an interesting look into the character’s psyche and makes for an interesting thought exercise as to the state of mind of other women at the time. Peggy clearly has some control over how she’s viewed at the SSR and her side investigation challenges that control. It forces her to examine her place within the agency, concluding that though she’s invisible to her colleagues, for the most part, she’d rather not be seen then looked at as helpless.

Consider two of Peggy’s colleagues, Jack Thompson and Daniel Sousa. Like Peggy, they’re war veterans, but the two approach the SSR’s sole female agent in very different ways. Thompson is all bravado, a blatant chauvinist who can’t even bother to get Peggy’s name right so long as he gets his coffee and lunch order placed correctly. Sousa, on the other hand, is more sympathetic to Peggy since he’s also the target of Thompson’s jibes because of his injury during the war. And while Sousa attempts to be the good guy, telling Jack to back off and treat Peggy with more respect, Peggy calls him on his white-knighting. He may think he’s doing the right thing, being a better man than the others, but there’s a more subtle form of sexism occurring. Peggy doesn’t need Sousa to come to her aid, she’s perfectly capable of defending herself. Assuming she needs defending is just another way of reinforcing the gender stereotype that women are incapable of taking care of themselves. In fact, the underestimation of women plays throughout the entire series as virtually every female character uses their perceived weakness to their advantage against men. Dottie hides the cold, Russian assassin behind a helpless doe-eyed mid-Western persona, Angie starts spilling fake tears to distract Thompson and Sousa, and Peggy frequently makes use of her invisibility within the agency as she conducts her side investigation into clearing Howard Stark. Though she’s loathe to use her second-tier status, it’s a tool nonetheless. It’s actually an interesting look into the character’s psyche and makes for an interesting thought exercise as to the state of mind of other women at the time. Peggy clearly has some control over how she’s viewed at the SSR and her side investigation challenges that control. It forces her to examine her place within the agency, concluding that though she’s invisible to her colleagues, for the most part, she’d rather not be seen then looked at as helpless.

At least with Thompson there’s something Peggy can fight against. He wears his prejudices on his sleeve, so changing his mind and proving her worth as an agent would of course mean showing competency during a field mission involving the Howling Commandos. And it really is the most effective turnaround because even though Peggy and Thompson do bond over being soldiers, Peggy ultimately relates to Thompson on a human level by showing sympathy and empathy when he comes clean about his experiences in the Pacific Theater. This isn’t the writers going “if woman, therefore motherly role” as a means of justifying their shared moment. This is about vulnerability. Peggy taking the lead after Thompson freezes in a firefight, and her giving him orders to snap him out of it, gives him, for the briefest of moments, some insight about the real Peggy Carter. The true strength of her character is her ability to have those feelings for someone who, for all intents and purposes, wouldn’t respond in kind. Peggy’s goal isn’t to belittle her colleagues or emasculate them for the sake of her own self-worth. As she says in the season finale, she knows her value, and it’s not about getting her name in the paper or recognition from a state congressman. For Peggy, it’s about getting the respect and trust of her colleagues; not as a woman but as an agent.

At least with Thompson there’s something Peggy can fight against. He wears his prejudices on his sleeve, so changing his mind and proving her worth as an agent would of course mean showing competency during a field mission involving the Howling Commandos. And it really is the most effective turnaround because even though Peggy and Thompson do bond over being soldiers, Peggy ultimately relates to Thompson on a human level by showing sympathy and empathy when he comes clean about his experiences in the Pacific Theater. This isn’t the writers going “if woman, therefore motherly role” as a means of justifying their shared moment. This is about vulnerability. Peggy taking the lead after Thompson freezes in a firefight, and her giving him orders to snap him out of it, gives him, for the briefest of moments, some insight about the real Peggy Carter. The true strength of her character is her ability to have those feelings for someone who, for all intents and purposes, wouldn’t respond in kind. Peggy’s goal isn’t to belittle her colleagues or emasculate them for the sake of her own self-worth. As she says in the season finale, she knows her value, and it’s not about getting her name in the paper or recognition from a state congressman. For Peggy, it’s about getting the respect and trust of her colleagues; not as a woman but as an agent.

What’s important to note about both Agent Carter and Parks and Recreation is that neither show treats its characters, male or female, like idiots. Peggy is exceptionally good at what she does but is still treated as a glorified secretary by her male peers. It’s not out of cruelty just misguided sentiments. Though she’s often frustrated by the men in the SSR or downright disgusted by any of Howard Stark’s shenanigans, Peggy never calls them incompetent. She, too, makes mistakes but we’re still rooting for her because we know what she’s capable of. And though we may desire comeuppance for some members of the SSR, the show is much wiser than that, presenting a snapshot of a bygone era that still holds relevance today.

Leslie Knope, however, could have easily become the female version of The Office‘s Michael Scott. Parks and Rec certainly owes its existence to The Office, but thankfully Leslie, as a character, was given much more substance than being a lovable goof. She is a lovable goof, by the way, but there’s no one on the show who ever questions her competence at her job or her intelligence because she’s a woman. If anything, Leslie’s hyper-competence and her extreme passion for governance often puts her at odds with the people of Pawnee and occasionally her friends and co-workers. At the same time, it’s Leslie’s passion for her work that leads her down the path to a ridiculously rewarding and awesome future.

The phrase “Be The Leslie Knope of Whatever You Do” is essential to what makes Parks and Rec and Leslie so special. From the beginning of the series, we know that Leslie is full of vim, vigor, and vitality for her work in the Parks Department. She shows excitement for a job that offers very little in the way of gratitude from the people she serves but Leslie isn’t necessarily looking for accolades. Her reward is helping people because she ultimately believes in the power of people coming together in order to accomplish a common goal. It’s why she loves working for the city. She gets to change people’s lives, whether they notice or not. What’s refreshing about Leslie’s consistent optimism is it’s never portrayed on the show as something we should pity her for. Leslie isn’t a character meant to be seen as pathetic because she doesn’t grasp the reality of her situation. The exact opposite is true. Leslie is very aware of how  she’s perceived by people, but it doesn’t deter her. If anything, she sees the complacency and apathy of those around her as a challenge, which she meets head on. She matches Ron Swanson’s anti-government paranoia and April Ludgate’s pessimism with openness and a helping hand and we cheer her on because, like Ron, April, or pretty much every person living in Pawnee, we see the greatness and the passion Leslie puts into everything she does and we want to apply that same passion to what we do in our own lives. We want to “be the Leslie Knope” of our own passions.

she’s perceived by people, but it doesn’t deter her. If anything, she sees the complacency and apathy of those around her as a challenge, which she meets head on. She matches Ron Swanson’s anti-government paranoia and April Ludgate’s pessimism with openness and a helping hand and we cheer her on because, like Ron, April, or pretty much every person living in Pawnee, we see the greatness and the passion Leslie puts into everything she does and we want to apply that same passion to what we do in our own lives. We want to “be the Leslie Knope” of our own passions.

To me, Leslie is the embodiment of the modern feminist. Not only does she show an exhausting amount of joy, confidence, and passion for her job, but she also has the ideal balance of career and family. The road towards this ideal, however, was not an easy one. At the beginning of the series, Leslie’s career goals often took precedence over her personal life – except for Ann because nothing comes between Leslie and Ann! – but once she met Ben Wyatt the priorities began to shift. There’s this prevailing myth that women have to choose between having a family or having a career, which is complete bull. Women don’t have to choose one or the other. They can have both if they put in the time. It’s about balance and in Ben Leslie found her balance. Like her philosophy that teamwork and helping people are the ultimate goals of government, so too did Leslie apply the same mindset to her relationship with Ben. Once they decided they were a team, that they were in it for the long haul, every decision was made by the Knope-Wyatt household committee. Thankfully Ben shared Leslie’s passion for government and civil service but he also shared a  passion for helping Leslie fulfill her dreams. It’s still a rare thing for a male character to put a female character’s wants and needs over his own in any form of media. If we see Leslie through Ben’s eyes, however, we know that her drive will propel them forward no matter what. Ben is no more sacrificing his goals than Leslie would if the situation were reversed. But it isn’t really a sacrifice for them. Whether it’s a position on the city council, Congress, Governor of Indiana, or President of the United States, Leslie and Ben are a team and they both get to enjoy the ride together.

passion for helping Leslie fulfill her dreams. It’s still a rare thing for a male character to put a female character’s wants and needs over his own in any form of media. If we see Leslie through Ben’s eyes, however, we know that her drive will propel them forward no matter what. Ben is no more sacrificing his goals than Leslie would if the situation were reversed. But it isn’t really a sacrifice for them. Whether it’s a position on the city council, Congress, Governor of Indiana, or President of the United States, Leslie and Ben are a team and they both get to enjoy the ride together.

This, of course, only scratches the surface of Parks and Recreation‘s legacy on television. Hopefully it’s the beginning of greater things for Agent Carter. Either way, we’ve been fortunate enough to let women like Peggy Carter and Leslie Knope into our homes. Their mark on us is what counts and if I were to venture a guess, I’m pretty sure there are going to be more girls and boys striving to be like Leslie and Peggy in the future.

The vampire as metaphor has had a fascinating staying power since Bram Stoker’s Dracula turned Eastern European folklore into a gothic tale of sexual repression and liberation. At times they’re feral beasts of horror or sexy, brooding heroes tortured by their own immortality. Or…Twilight. The point is vampires, while we may associate them with certain traits, can be as powerful, vulnerable, and insightful as the narrative allows. Their monstrosity is subjective, giving storytellers ample room to explore the nature of vampires and the world around them. In A Girl Walks Home Alone At Night, writer and director Ana Lily Amirpour crafts a vampire that is neither virtuous nor villain, but somewhere in between. Though she is what we’d typically classify as a “monster” it becomes clear that Bad City has more than its fair share of demons.

their own immortality. Or…Twilight. The point is vampires, while we may associate them with certain traits, can be as powerful, vulnerable, and insightful as the narrative allows. Their monstrosity is subjective, giving storytellers ample room to explore the nature of vampires and the world around them. In A Girl Walks Home Alone At Night, writer and director Ana Lily Amirpour crafts a vampire that is neither virtuous nor villain, but somewhere in between. Though she is what we’d typically classify as a “monster” it becomes clear that Bad City has more than its fair share of demons.

In the Iranian town of Bad City, The Girl (Sheila Vand) stalks the streets at night, preying upon the worst of the worst in a city where death and loneliness thrive. Her curiosity, however, leads her to an unlikely romance with Arash (Arash Marandi), a young man struggling to do what’s “right” when nothing is as clear-cut as it seems. As their lives become more intertwined the truth becomes harder to hide.

Billed as the first Iranian vampire Western, A Girl Walks Home Alone At Night exists in a deliberately nebulous space that keeps it open to interpretation. One can view it through a feminist lens as The Girl primarily attacks men who bully and exert their own power on others, mainly coming to the defense of a prostitute, Atti (Mozhan Marnò), who’s connected to both Saeed (Dominic Rains) the local drug dealer and Arash’s addict father, Hossein (Marshall Manesh). There’s also commentary to be gleaned from the frequent shots of oil rigs, the open, almost casual display of dead bodies in a ditch, and the stagnant feel of Bad  City that appears to be stuck in several time periods as the director’s feelings on Iran and the country’s culture. Amirpour, however, finds the interpretation to be more reflective of the interpreter. As for her own view on the themes in her film, she said:

City that appears to be stuck in several time periods as the director’s feelings on Iran and the country’s culture. Amirpour, however, finds the interpretation to be more reflective of the interpreter. As for her own view on the themes in her film, she said:

In this case, it’s really about loneliness. A vampire is the loneliest, most isolated cut-off type of creature. She also has something very bad to hide about who she is and it’s a brilliant disguise. It becomes a way to stay under the radar and underestimated. There are a million ways to read it. It will tell you more about you than it does about me. [Source: LA Times]

In regards to the disguise element, Amirpour is referring to the chador that The Girl wears in the film. A symbol of systemic oppression towards women in the Middle East, the chador and The Girl’s use of it as a means of making herself an unassuming presence have been the focus of many reviews; proof positive that The Girl is subverting the nature of the garment and using it as a tool of empowerment. The chador was apparently what inspired Amirpour to make a movie about a vampire, saying:

In Iran, I have had to wear a hijab [headscarf], and personally I find it completely suffocating. I don’t want to be covered up in all that cloth. But there was something about the chador though. It’s made of a different fabric. It’s soft and silky and it catches the air. When I put it on, I felt supernatural. But I also get to take it off. [Source: LA Times]

There are several scenes in the movie where Amirpour shows the ethereal and supernatural quality of the chador when The Girl is out on the town. One particular moment that comes to mind is The Girl riding a skateboard down an empty street, letting the wind catch the fabric. It’s one of the rare moments where she naturally smiles, experiencing a strange sense of freedom. Framed within the shot, the chador simultaneously resembles bat-like qualities associated with vampires and the silhouette of a superhero’s cape. It’s a beautiful display of the film’s cinematography that also highlights the prevailing theme of concealment. Interestingly enough, when The Girl and Arash meet and speak to each other for the first time, Arash – high as a kite – is wearing a Dracula costume. It’s a brilliant juxtaposition that the two begin to form their romance when both are essentially in disg uise.

uise.

Where A Girl Walks Home Alone At Night really shines is in its style and mood. Filmed in black and white, Amirpour imbues Bad City and the people living there with a sense of style that maintains an air of retro coolness but is also indicative of a culture mired in crime and death. Bad City is stuck somewhere between the old and the modern as are most of its denizens. The opening shot of Arash establishes his greaser/James Dean aesthetic right down to the vintage car he drives. The Girl dances to 80s synth-pop but her short hair, striped shirt, and black leggings give off a mod Audrey Hepburn meets Uma Thurman in Pulp Fiction vibe. The influence of Quentin Tarantino is hard to miss, so the look of The Girl was probably intended. Saeed has a very 80s look about him as well, sporting a track suit, gold chains, and living in an apartment that even the Land of Oz would say needs to be toned down. The stylistic choices are another way of commenting on the disparity of wealth in a place like Bad City where there’s a clear contrast between the rich and the poor but even the lower classes prey upon each other. Filmed in Bakersfield and Taft, California as stand-ins for Iran, Amirpour shows the industrial, ruined state of Bad City, telling us with only an establishing shot of the distant oil rigs exactly why everything has gone to shit.

Bu t it wouldn’t be a vampire movie without an element of horror to it, right? Oh, yeah…Twilight. Anyway, Amirpour keeps the horror to a minimum. Yes, The Girl feeds, but the strength of film lies in the suspense. We don’t meet The Girl until about fifteen minutes into the film. In that time, we’ve met the rest of the cast and we see just how destitute Arash and his father are and how Saeed uses drugs and intimidation to get what he wants. When The Girl finally shows up, she’s at a distance, watching Saeed geting a blowjob from Atti after verbally and physically abusing her. From there on, Amirpour establishes a pattern. The Girl shows up and begins to stalk her prey. She’s unassuming and yet unnerving, constantly staring with wide eyes that are simultaneously curious and cold. Vand plays the part expertly. The Girl is a mostly silent character, which means all of the performance is in Vand’s eyes and movement. As the tension builds in the excruciatingly long shots and pauses between The Girl and her next meal – heightened by the sound of footsteps amped up to keep the audience as nervous as possible – Vand makes us feel and understand what The Girl is going through. The same is true of her scenes with Marandi. Though Arash is the more talkative of the two, there are several long pauses where the two are merely staring at each other, conveying everything with their eyes and making us believe that the two have made a connection. It’s the final ten minutes, however, where the two give us the most nerve-wracking moments of intensified suspense, all without saying a word. All because of a cat.

t it wouldn’t be a vampire movie without an element of horror to it, right? Oh, yeah…Twilight. Anyway, Amirpour keeps the horror to a minimum. Yes, The Girl feeds, but the strength of film lies in the suspense. We don’t meet The Girl until about fifteen minutes into the film. In that time, we’ve met the rest of the cast and we see just how destitute Arash and his father are and how Saeed uses drugs and intimidation to get what he wants. When The Girl finally shows up, she’s at a distance, watching Saeed geting a blowjob from Atti after verbally and physically abusing her. From there on, Amirpour establishes a pattern. The Girl shows up and begins to stalk her prey. She’s unassuming and yet unnerving, constantly staring with wide eyes that are simultaneously curious and cold. Vand plays the part expertly. The Girl is a mostly silent character, which means all of the performance is in Vand’s eyes and movement. As the tension builds in the excruciatingly long shots and pauses between The Girl and her next meal – heightened by the sound of footsteps amped up to keep the audience as nervous as possible – Vand makes us feel and understand what The Girl is going through. The same is true of her scenes with Marandi. Though Arash is the more talkative of the two, there are several long pauses where the two are merely staring at each other, conveying everything with their eyes and making us believe that the two have made a connection. It’s the final ten minutes, however, where the two give us the most nerve-wracking moments of intensified suspense, all without saying a word. All because of a cat.

Currently in limited release, A Girl Walks Home Alone At Night, is well worth your time if you have any interest in the work of upcoming directors like Amirpour or desire something more substantial from your vampire-themed entertainment. If you can’t find a showing nearby, there are two issues of a comic book written by Amirpour available for purchase that give you some background on The Girl. Hopefully that will tide you over until the film comes out on VOD and DVD/Blu-ray.

The urge to name this Love in the Time of Wonder Woman was so strong, but I resisted the impulse. While there was an ease with which the rejected article title came, it didn’t quite capture everything I wanted to cover in talking about the 35 issue run of Wonder Woman. In the three years since the New 52 launched, the creative team of writer Brian Azzarello, artists Cliff Chiang, Tony Akins, Goran Sudzuka, colorist Matthew Wilson, and letterer Jared K. Fletcher crafted a new origin for DC Comics’ first female superhero, one steeped in the old mythology of the Greek Pantheon but intent on forging ahead to create a new mythology with Wonder Woman leading the way.

For the record, though, if you’re looking for a place that will at least consider making references to the works of Gabriel García Márquez….Bam. This girl.

Moving on.

As, presumably, the introduction for new readers via the “soft reboot” of the New 52, the creative team were faced with the task of making Diana’s story within her corner of the DC Universe fantastical, entertaining, and above all else relatable. In order to do so, Azzarello and Chiang dove into the core tenants of Wonder Woman’s character as established by her creator, William Moulton Marston, and used those elements to build a story around two essential questions: Who is Wonder Woman and what does she stand for? The answer lies in the simplest yet most complex word, love. From love springs a multitude of emotions – mercy, compassion, tolerance, anger, rage, and forgiveness – all of which hinder and guide Wonder Woman in her personal journey of discovery, a journey she doesn’t make alone. Though love ends up being the answer, how Diana frames her revelations is within the context of family; her biological family of gods and demigods as well as the family she builds with her friends and rebuilds amongst the Amazons. The consequences of such a framework, however, brings about the destruction of Marston’s “paradise”, but I think that was Azzarello’s intention all along. In lieu of paradise, of some perceived utopia, Azzarello posits that family and community should be the goal and only by understanding and submitting to love can such a goal be accomplished.

Before we go any further, and because this article will mostly be addressing Wonder Woman from a writing and thematic perspective, I wanted to talk about Cliff Chiang’s artwork on the book. Of all the redesigns in the New 52, Chiang’s Wonder Woman continues to be my favorite and is definitely in my top five versions. Chiang manages to capture the Amazon in Diana – tall, athletic, broad shoulders – making us believe that this is a woman who’s trained her whole life as a warrior. Her athletic aesthetics, however, don’t come at the cost of her femininity. Diana is gorgeous but Chiang deftly keeps away from sexualizing not just Diana but most of the book’s female characters.

Before we go any further, and because this article will mostly be addressing Wonder Woman from a writing and thematic perspective, I wanted to talk about Cliff Chiang’s artwork on the book. Of all the redesigns in the New 52, Chiang’s Wonder Woman continues to be my favorite and is definitely in my top five versions. Chiang manages to capture the Amazon in Diana – tall, athletic, broad shoulders – making us believe that this is a woman who’s trained her whole life as a warrior. Her athletic aesthetics, however, don’t come at the cost of her femininity. Diana is gorgeous but Chiang deftly keeps away from sexualizing not just Diana but most of the book’s female characters.

The modern, or ancient, redesigns of the Greek Pantheon are probably my favorite aspect of the book from an artistic  standpoint. Instead of keeping to the stereotypical depiction of the Greek gods, Chiang makes them the embodiment of their particular territory or job. Hermes the Messenger has the visage of a humanoid bird, Artemis the goddess of the hunt and the moon glows brightly while sporting antlers, looking like a marble statue, and Poseidon, lord of the seas, is a gigantic fish-like creature, a great and powerful reflection of his domain. My favorite design is probably Strife. Though her only otherworldly aspect is her purple skin, Strife looks exactly like her name. The shaved head, heavy makeup, and slashed form-fitting dress give readers an immediate sense of unease, that anything involving her will lead to trouble. Wonder Woman is definitely one of the most beautiful books from DC. It’s vibrant and bursting with energy and color thanks to Chiang and colorist Matthew Wilson.

standpoint. Instead of keeping to the stereotypical depiction of the Greek gods, Chiang makes them the embodiment of their particular territory or job. Hermes the Messenger has the visage of a humanoid bird, Artemis the goddess of the hunt and the moon glows brightly while sporting antlers, looking like a marble statue, and Poseidon, lord of the seas, is a gigantic fish-like creature, a great and powerful reflection of his domain. My favorite design is probably Strife. Though her only otherworldly aspect is her purple skin, Strife looks exactly like her name. The shaved head, heavy makeup, and slashed form-fitting dress give readers an immediate sense of unease, that anything involving her will lead to trouble. Wonder Woman is definitely one of the most beautiful books from DC. It’s vibrant and bursting with energy and color thanks to Chiang and colorist Matthew Wilson.

Okay, back to the rest of the article.

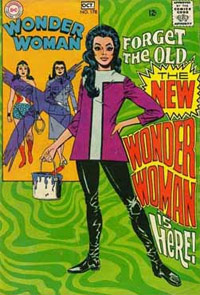

The origin of Diana of Themyscira is often one of the first elements tackled when a new creative team takes over the book or DC feels like rebooting. Unlike Krypton blowing up or Thomas and Martha Wayne being killed in Crime Alley, Wonder Woman’s backstory of being molded from clay and entering “Man’s World” has gone through several iterations since she first appeared in 1941. Because of this malleability, Wonder Woman tends to embody the attitudes of women within the modern world –  depending on who’s writing – but each retelling and reinterpretation is hit or miss depending on a number of factors, one of the most prominent being the socio-political climate. When Diana lost her powers in the 1960s in order to make her seem more like the modern day woman it was met with scorn from feminists like Gloria Steinem who accused the creative team of taking the most powerful female superhero and stripping her of her powers. The intention may have been to make Wonder Woman relevant to the modern readership, the change was inspired by Diana Rigg’s Emma Peel in The Avengers television show, but the response proved that, like Superman, Wonder Woman’s core audience of female readers looked to her as an ideal, something to strive for and emulate.

depending on who’s writing – but each retelling and reinterpretation is hit or miss depending on a number of factors, one of the most prominent being the socio-political climate. When Diana lost her powers in the 1960s in order to make her seem more like the modern day woman it was met with scorn from feminists like Gloria Steinem who accused the creative team of taking the most powerful female superhero and stripping her of her powers. The intention may have been to make Wonder Woman relevant to the modern readership, the change was inspired by Diana Rigg’s Emma Peel in The Avengers television show, but the response proved that, like Superman, Wonder Woman’s core audience of female readers looked to her as an ideal, something to strive for and emulate.

William Moulton Marston addressed this need for an iconic hero for women and girls in the 1943 issue of The American Scholar, writing:

Not even girls want to be girls so long as our feminine archetype lacks force, strength, and power. Not wanting to be girls, they don’t want to be tender, submissive, peace-loving as good women are. Women’s strong qualities have become despised because of their weakness. The obvious remedy is to create a feminine character with all the strength of Superman plus all the allure of a good and beautiful woman.

Marston very much believed that the new world order would eventually be run by women and used Wonder Woman as “psychological propaganda for the new type of woman who should…rule the world”. Unlike the violent tendencies of men and boys, girls and women had a greater emotional capacity that, he believed, made them stronger and better leaders. Wonder Woman was a figurehead for them to rally behind, a Pygmalion creation meant to embody all that women were capable of. Making Diana the princess of the Amazons who inhabited Paradise Island solidified Marston’s vision of a utopian culture of peace and prosperity run entirely by women. By venturing out into “Man’s World”, Wonder Woman brought those sensibilities  with her as she fought Nazis and enemies on the home front, teaching and showing girls that violence wasn’t the only option but should more forceful actions need to be taken they were strong enough to break the chains or ropes that bound them. For all of the bondage imagery shown in Marston’s run, there were plenty of metaphors to be gleaned regardless of what “Dr.” Wertham thought.

with her as she fought Nazis and enemies on the home front, teaching and showing girls that violence wasn’t the only option but should more forceful actions need to be taken they were strong enough to break the chains or ropes that bound them. For all of the bondage imagery shown in Marston’s run, there were plenty of metaphors to be gleaned regardless of what “Dr.” Wertham thought.

Since Marston, the depiction of Paradise Island, later named Themyscira in the 1987 relaunch, and the Amazons have gone through as many changes as Wonder Woman. While Marston envisioned utopia with an all-female society, the exploration of Amazonian culture is a fascinating aspect of the Wonder Woman canon since the environment she grows up in acts as a reflection of the character. Some writers have utilized it beautifully (The Circle from Gail Simone, Terry Dodson, and Rachel Dodson) and others not so much (Amazons Attack! from Will Pfeifer and Pete Woods). How much Diana embraces or fights against her Amazonian upbringing is no different than how any person might face their heritage and family. And it’s here where Azzarello’s stamp on Wonder Woman takes a sharp turn for better or for worse.

The two most controversial aspects of Azzarello’s reboot were the changes made to Diana’s origin and the Amazons. In the New 52, Diana was no longer molded from clay and blessed with life from the gods. Instead it was revealed that she was the biological daughter of Hippolyta and Zeus, making her a demigod. After finding her mother turned to stone and her sister Amazons turned into snakes as punishment from Hera, Diana becomes immersed in her godly family of half brothers and sisters, uncles and aunts. In the process, she receives one final revelation about the Amazons: to continue populating the island with female warriors, the Amazons took over ships with men on board, had sex with them, kept the daughters and gave the sons to Hephaestus.

The two most controversial aspects of Azzarello’s reboot were the changes made to Diana’s origin and the Amazons. In the New 52, Diana was no longer molded from clay and blessed with life from the gods. Instead it was revealed that she was the biological daughter of Hippolyta and Zeus, making her a demigod. After finding her mother turned to stone and her sister Amazons turned into snakes as punishment from Hera, Diana becomes immersed in her godly family of half brothers and sisters, uncles and aunts. In the process, she receives one final revelation about the Amazons: to continue populating the island with female warriors, the Amazons took over ships with men on board, had sex with them, kept the daughters and gave the sons to Hephaestus.

Many a critic and Wonder Woman fan cried foul on this change in particular since Azzarello essentially turned the Amazons into rapists. I’m not here to argue that point because it’s a valid one, but I think I understand why Azzarello made the changes. Again, Marston saw an all-female society as utopia, it’s why he named the home of the Amazons Paradise Island. But anyone who’s studied the concept of utopia knows that it’s never an achievable form of society despite what the creator desires. There are plenty of historical examples and it’s rare that fiction ever depicts a utopian society as anything less than sinister. Azzarello is yet another author in this category. Prior to the discovery of Themyscira’s repopulation program, Azzarello laid the foundation that all was not well on Paradise Island. Wonder Woman was already living in London, away from the island, and her return with Zola and Hermes, plus the appearance of Strife, brings out the underlying antagonism of some of the Amazons towards Diana. Referring to her as “clay” in a derogatory manner, it’s clear that peace, tranquility, and love aren’t always present.

Azzarello is no stranger to tackling the darker side of comic book characters. Some of his best works for DC are Joker, Lex Luthor: Man of Steel, and Superman: For Tomorrow, all of which highlighted essential aspects of the characters from Azzarello’s point of view. With Wonder Woman, Azzarello is arguing that Marston’s utopia is fallible and a myth in its own right. An all-female society is no less effective than an all-male society. The Amazons are, after all, still human. By distancing themselves from “Man’s World” they’ve lost their hold on an inclusive community. This is what makes Wonder Woman so  essential. She’s the bridge between the Amazons and the outside world, but only through taking the journey of coming to terms with her own identity and what it means to be Wonder Woman, a demigod, the God of War, and the new Queen of the Amazons, does she possess the wisdom to rebuild her family on Themyscira. She cannot separate these worlds any more than she can separate her identity. They’re all parts of a whole and by melding them she’s made stronger. It’s why she pleads with her sister Amazons to accept their brothers and protect Zola and her baby against the First Born’s army. They will be stronger as a whole, as a family, and it is simply the right thing to do.

essential. She’s the bridge between the Amazons and the outside world, but only through taking the journey of coming to terms with her own identity and what it means to be Wonder Woman, a demigod, the God of War, and the new Queen of the Amazons, does she possess the wisdom to rebuild her family on Themyscira. She cannot separate these worlds any more than she can separate her identity. They’re all parts of a whole and by melding them she’s made stronger. It’s why she pleads with her sister Amazons to accept their brothers and protect Zola and her baby against the First Born’s army. They will be stronger as a whole, as a family, and it is simply the right thing to do.

Throughout Azzarello and Chiang’s run, love is shown to be the root of Diana’s decisions and at the center of the conflict between her and the First Born. In their final confrontation, Diana ties it all together from a thematic perspective when she tells the First Born that his demand for love and power will never result in victory because he doesn’t understand that love is about submission. There have been several instances in the book where Diana was put into a position of submission – marrying Hades, tricking Artemis into “winning” a fight, the First Born’s proposal – but none of them were made out of an actual act of love. Compare this to what Diana has personally done out of genuine feelings of love; protecting Zola and her baby, forgiving a mortal Hera, helping Hades learn to love himself, and reuniting her sister and brother Amazons. She shows compassion, mercy, and forgiveness towards others because, at her core, her love for all living things is infinite. Fittingly, her last act in the final issue is an actual submissive plea to Athena to spare Zola’s life. By submitting to love and appealing to Wisdom, Wonder Woman shows us her true heroism.

Throughout Azzarello and Chiang’s run, love is shown to be the root of Diana’s decisions and at the center of the conflict between her and the First Born. In their final confrontation, Diana ties it all together from a thematic perspective when she tells the First Born that his demand for love and power will never result in victory because he doesn’t understand that love is about submission. There have been several instances in the book where Diana was put into a position of submission – marrying Hades, tricking Artemis into “winning” a fight, the First Born’s proposal – but none of them were made out of an actual act of love. Compare this to what Diana has personally done out of genuine feelings of love; protecting Zola and her baby, forgiving a mortal Hera, helping Hades learn to love himself, and reuniting her sister and brother Amazons. She shows compassion, mercy, and forgiveness towards others because, at her core, her love for all living things is infinite. Fittingly, her last act in the final issue is an actual submissive plea to Athena to spare Zola’s life. By submitting to love and appealing to Wisdom, Wonder Woman shows us her true heroism.

I know I’m not the only one who has strong feelings towards Azzarello and Chiang’s run on the book, but I feel it’s been consistently one of the strongest coming out of DC and I’m sad to see the creative team go. There’s certainly plenty to unpack within those 35 issues, but this is just a portion of what I’ve taken away from it. But I’m interested to know what other people think.

Just, ya know, be civil. We’re all friends here.

Sam talks with the Ink-Stained Amazon herself, Jennifer Stuller. The two talk about women as they’re portrayed in movies, television, and comic books and talk about the future of women in media.

Sam talks with JoJo Stiletto, Professor of Nerdlesque, about all things burlesque and the show Whedonesque Burlesque celebrating the works of Joss Whedon.